Broc, Switzerland

1979

This isn’t where the story begins, it’s just where I begin to tell it.

I am a single, 27-year-old chemical engineer, born in New York City, living in the Swiss boonies. I have the politically impossible job of trying to influence the approach of my more senior Swiss counterparts in the process of making chocolate. As should have been expected, it’s not going well.

My office-mate Sallin is drunk again, this morning. There is wildness in his reddened eyes, his hair is a mess and his breath stinks. His movements are nervous and sloppy, his speech punctuated with impulsive half-laughter. He seems to inhale a whole pack of cigarettes without exhaling. The stench of smoke and gin drifts across our adjoining desks and makes my eyes water. He has tried to mask the booze with strong cologne, but that only makes it worse. It’s 9 AM, he is a nice man and he is killing himself.

He is weak, too weak to confront his problems or to stand up for himself. Too weak and too fried to generate any constructive thought. The wildness in his eyes is fear, not fury. Anger might at least motivate him to fight back. Sallin only drinks.

Once, he scared himself into drying out for a while. Early one Saturday morning he totaled his car. His passenger, his 9-year-old son, got banged up in the bargain. He was too drunk at the time to be able to recall anything that had happened, and afterwards, he couldn’t even remember the location of the accident. He could only recall his car, rolling down a hillside, as if in slow motion, and no more. He felt nothing. It scared him enough to make him quit drinking for a few weeks.

The car was uninsured for collision, and now Sallin is depressed. It is summer, his children are out of school, and everyone is leaving on vacation. But for Sallin and his family there is to be no vacation, this year or next. The money has been spent on replacing the wrecked Citroen.

Sallin’s family seems pleasant enough, but who knows about what goes on behind closed doors? His job is boring, his problems are obvious to everyone, and he has no hope of ever advancing. He rents a modest 3-bedroom apartment in town. He is 42 and has little to show for it.

His greatest pleasures in life are going on his annual two-week army reserve duty and going on vacation with his family. In Switzerland everyone does army reserve duty until age 45, and for two weeks a year Sallin gets away from his real life, driving a truck by day, drinking in the pub and singing Swiss songs with his comrades by night. It sounds like summer camp for nominal grown-ups.

August is vacation month in Europe and last year he took the family camping in Yugoslavia. This year there isn’t even that to look forward to.

So Sallin is drinking again. 9 AM and half in the bag. If he has to kill himself, I wish he wouldn’t do it in front of me.

I know I will be transferred again fairly soon. This will spare me having to witness the final act and will allow me to imagine some happier outcome. When I leave, I will wish him the best of luck, maybe even mustering some sincere optimism. Then, if I am lucky, no one will ever tell me what has happened to him, and I will assume that nothing has changed. The current moment will be frozen in time, so I won’t have to think about the almost certain sad events to come. In my mind, Sallin may still be drunk by 9 in the morning, but the accident remains a past event and things just never get worse.

With a little imagination, I might even conjure up a dreamy vision, two years hence: Sallin and family on vacation again, motoring off into the Yugoslavian sunset, fade to black, roll end credits, play uplifting music.

But long before any of that happens I will be transferred. I’ll be leaving this situation behind. There seems to be no way I can make a difference.

So I’ll move on. Everything will change and nothing will.

* * *

New York, New York

1973

I began my engineering career in June of 1973 working at Ebasco Services, in lower Manhattan. They specialized in electric power plant design and I was their newest Water Treatment Engineer. I was ready to set the world right. I would purify our natural waterways and make the Earth good again. The pay wasn’t bad either.

“This is it”, I thought, perspiring lightly in the crowded rush-hour B Train on the way to my first day of work. “I have arrived.” I had received five job offers before leaving engineering school, but this one seemed to best meet all my criteria. I would be working in a professional setting in my field of interest, I would be getting a great salary and benefits package, and just as importantly, I would be staying in New York.

I was only a week away from moving into a new studio apartment in Staten Island, and two weeks away from my first “big” paycheck. In a few months I would order my first new car, a red 1974 Ford Mustang II. Everything was perfect. Every goal seemed within reach.

But things often don’t turn out as expected. Yes, I would move into the new apartment, get the big paycheck and even buy the new red car. But the job was awful.

Environmental improvement was not on the agenda. Protecting the plant’s equipment from the water it sucked out of the river to cool the power plant reactor was the main goal, and I was given precious little to do that might help to accomplish even that. Instead, I sat with two other recently hired engineers, in an office on an otherwise empty floor, where we were promptly forgotten.

My boss was away for several weeks, at the time of my arrival, and when he returned, he was too busy to deal with me. While logic and reason might suggest that no private sector enterprise, dedicated as it must be to turning a profit, would want to pay someone a substantial salary to do nothing, that is exactly what was happening. It was nonetheless profitable for the company.

Regardless of my inactivity, every hour of my time was being billed to the Pennsylvania Power & Light Company, for whom Ebasco was building a new power plant. They, in turn, presumably worked it into their rates for electric power consumers in Pennsylvania. So maybe ten million people in Pennsylvania each paid me a hundredth of a cent a month to do nothing. They didn’t seem to mind or even notice. I sat at my desk in my three-piece suit reading the paper, and picking horses to bet on at OTB during my lunch break.

But I was not content to just sit there, idling away the time to get paid. Eventually I made enough noise to be noticed and was assigned the task of reviewing bids for some storage tanks for water treatment chemicals. I went through quotation documents, line by line, to make sure each bid was based precisely on the specifications someone in our company had written. I understood very little of what these specifications meant, and there was no one to explain them to me.

I was 21 years old and was rapidly becoming a paper-pusher. I looked around and saw people who had been working there for five years doing exactly what I was doing now. Bored, lazy and useless is no way to go through life, and I’d had my fill of that already as a student. I was a couple of dollars ahead on the horses, and the people of Pennsylvania were a couple of thousand behind on me.

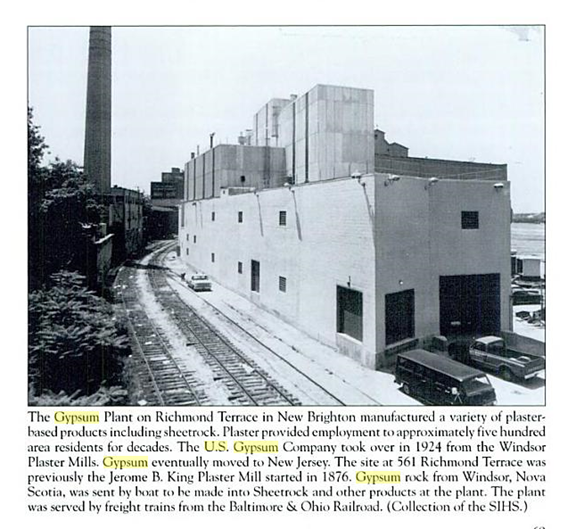

Eight weeks into my professional career, I was already breaking records. “We’ve never had anyone resign so quickly before”, the guy from Personnel told me. I took a small pay cut and accepted another of my original job offers, working as a project engineer at the U. S. Gypsum Company mill, across New York harbor in Staten Island. I hung up the three-piece suit and never wore it again.

My friend, Harry, stayed on at the Water Treatment Department, and for all I know he spent his whole life there. For all I know, for the rest of his life, he still bet on horses other people picked for him and he still grew pot in garbage cans under Grow-Lights in his basement. After the Fall harvest he cleaned out the garbage cans and made beer.

I moved on.

I left the whole situation frozen, there, in some sealed compartment in Time, where it stays, unchanging, forever. Like visions of past girlfriends who remain young and beautiful, never aging even a single day.

* * *

Broc, Switzerland

1979

Sometimes, late on lonely nights, the past pulls at me. Then all the old faces reappear, the lost friends, the departed, the estranged family, the mentors and teachers, the adversaries and the lost lovers. All the old dreams are reawakened, then, whispering in my ear that Time is passing, and if I don’t move on soon, I will be stuck in the middle of nowhere forever.

I have to move on…

* * *

Staten Island, NY

1973

They issued me safety glasses, a pair of stiff, steel-toed and capped black leather safety shoes, and a brown fiberglass hardhat. They were all uncomfortable. Within minutes of entering the world of the U. S. Gypsum New Brighton plant, I had already unwittingly stepped into a pile of white dust that dried out the skin on my right foot and would eventually make it crack. I was not disheartened, however, and it was the least of a long list of things about this new world to which I was oblivious.

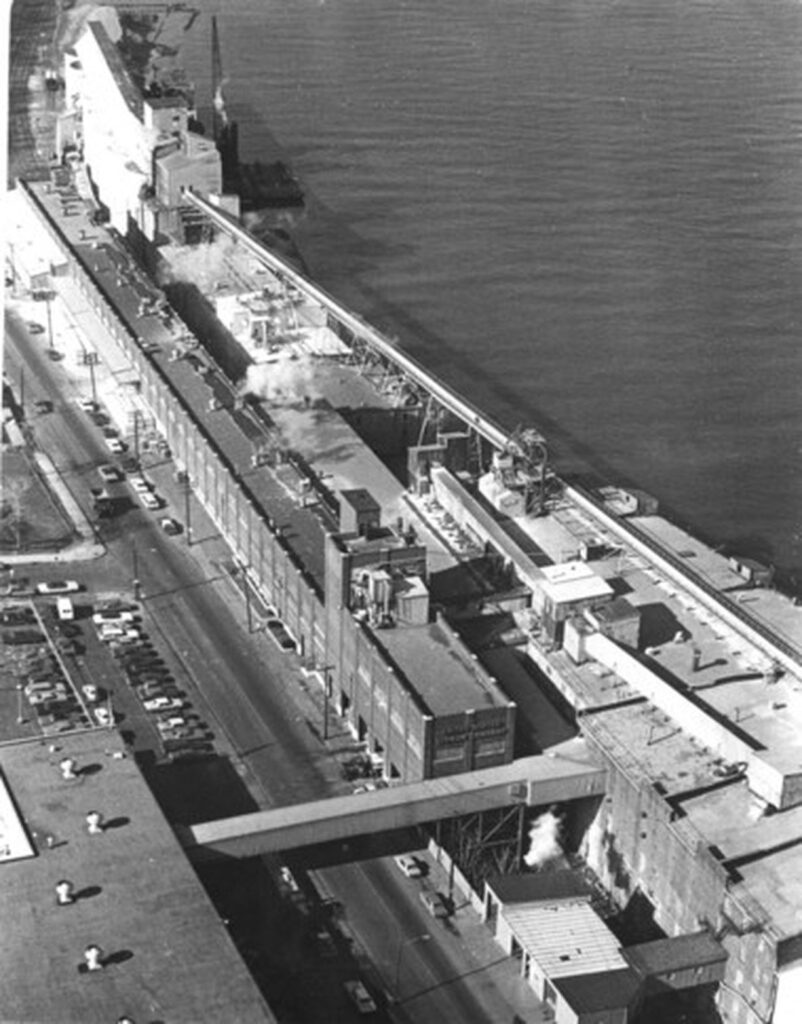

The turn-of-the-century gypsum mill was a Wonderland, unlike any place I had been or seen before. It stood on a steep, constricted slope between Richmond Terrace and the Kill Van Kull, a narrow tidal strait off New York Harbor. It was an odd string of mismatched buildings and structures, strung along a 100-yard wide strip nearly three quarters of a mile long.

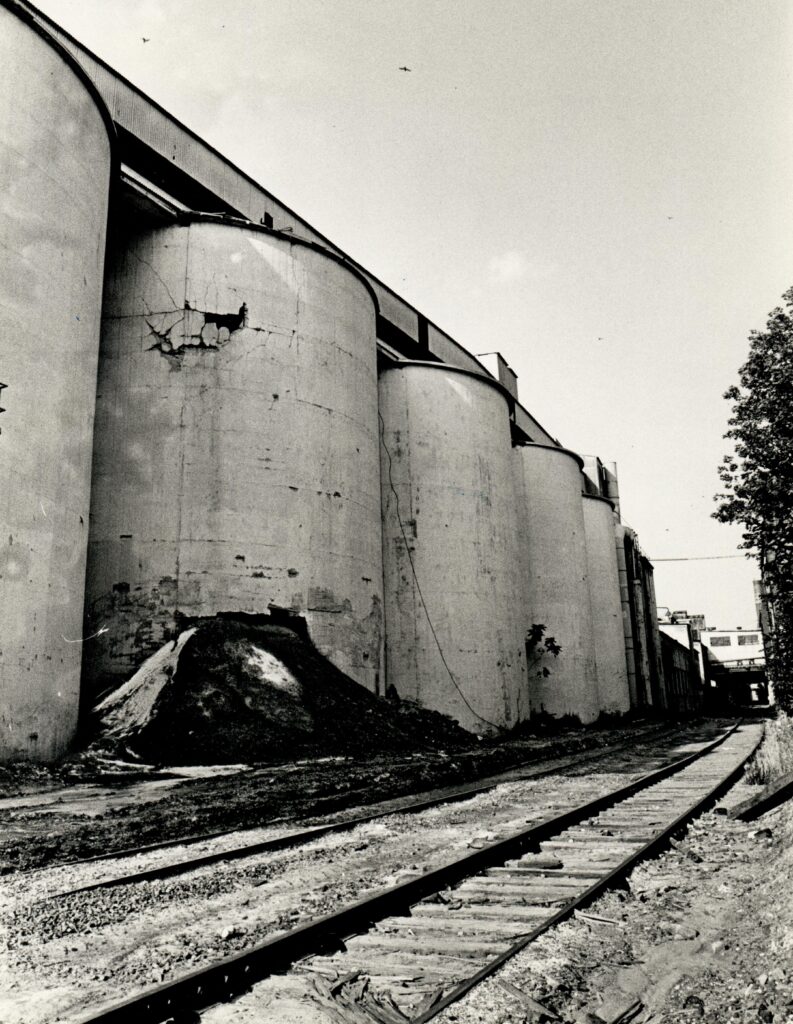

The first floor was at water level, where ships full of dark, white and anhydrite gypsum rock from Nova Scotia unloaded their cargo. The rock was then conveyed by a bucket elevator up into the top of one of the eight 50-foot diameter concrete silos, each of which was assigned to a specific grade of raw rock. One of the two anhydrite silos was plugged solid, the result of an operator error that had mixed anhydrite with dark rock, causing them to set up like concrete. It would take 8 months of focused effort, jack hammering, drilling and compressed carbon dioxide gas blasting to clear the silo, under the direction of a young engineer, Mike Tomasello. Mike was one year my senior, and we quickly became friends, as we shared a common situation. We would spend a fair portion of the next year in various bars.

One of my first encounters with Mike was in the conveyor bridge above the plugged silo, where he was discussing safety equipment and procedures with his demolition crew. There was plenty of reason for caution and concern. The process started with drilling holes into the fused gypsum, which was piled up 70 feet deep above the silo floor. Cylinders of highly compressed carbon dioxide gas were then dropped into the holes and were triggered remotely to set off a series of small explosions. When the charges were properly placed, several tons of rock would be broken up from the silo’s solid mass. In three months of work, the crew had opened a 10-foot-wide hole running the full height of the silo, directly above an opening that had been cut into the side of the silo. The strategy was to keep blowing up the rim of the hole and dropping the loosened rock down to the opening, where a bulldozer could enter and clear it out. Additional loosening of the rock was done using jack hammers.

The potential for disaster of working with explosive charges in an enclosed space 70 feet above the ground, along with the uncertainty of the footing while jack hammering partially blown-up rock at that height, was obvious. So Mike was lecturing his laborers again regarding safety protocols, but some of them just weren’t having any of it.

“I don’t believe in any of this safety shit”, one of them said. “When your number is up, it’s up”. Mike didn’t look happy.

“I could use all the safety equipment in the world and then just jump out this window”, he continued, leaning and taking a half-step in that direction.

“Well DON’T DO THAT!” Mike quickly commanded, clearly thinking there was half a chance the guy might actually keep going. A cold breeze blew in off the Kill van Kull through the unglazed opening.

“I’m just saying, when your number is up, it’s up,” the man repeated. “That’s all I’m saying.”

After 8 months of focused effort, the silo was finally cleared. Even so, it would never be used again.

On a different day, Mike and I were walking through the Mill and he saw a worker pouring waste oil into a hole in the factory floor.

“What do you think you’re doing?” Mike demanded.

“I’m getting rid of this dirty oil”, the man replied, matter-of-factly. “I’m just pouring it down that hole and it disappears.”

“This building sits right over the harbor”, Mike snapped at him, incredulously. “Where do you think that oil goes?”

“It just goes down that hole and disappears”, the man answered with an expression of disbelief. “I always just pour it down that hole.”

The man couldn’t understand why a bright young man with an engineering degree would have such a hard time understanding something so simple. Nonetheless, Mike firmly instructed him never to do that again, issuing him an “AVO”, a written form that stood for “Avoid Verbal Orders”. There was a carbon copy that remained in Mike’s AVO book after he tore out the original and handed it to the man.

Later, Mike would mention the incident to the plant’s environmental engineer, John White, with whom I shared office space in the Plant Engineering Department. John winced, but not so hard as to imply he had never heard anything that stupid before.

* * *

The US Gypsum New Brighton plant ran two rotary calciners like the one shown here.

From the silos, the dark rock was conveyed to the Mill, Building #1, where it passed through crushing and screening machines at a rate of 50 tons per hour. The fist-sized rocks that emerged were then fed into the rotary calciners, huge steel cylinders a man’s height in diameter and several hundred feet long. The cylinders were pitched at a shallow angle, and as they slowly rotated, the rock tumbled downhill to the exit at the far end. Six hundred fifty degree air rushed upward through the massive rotating tubes in the opposite direction, cooking off just the right amount of the gypsum rock’s chemically-combined water to leave behind raw plaster. From there it was conveyed to various departments, like the wallboard plant, where it would be used to make Sheetrock. The roar of the whole operation was deafening.

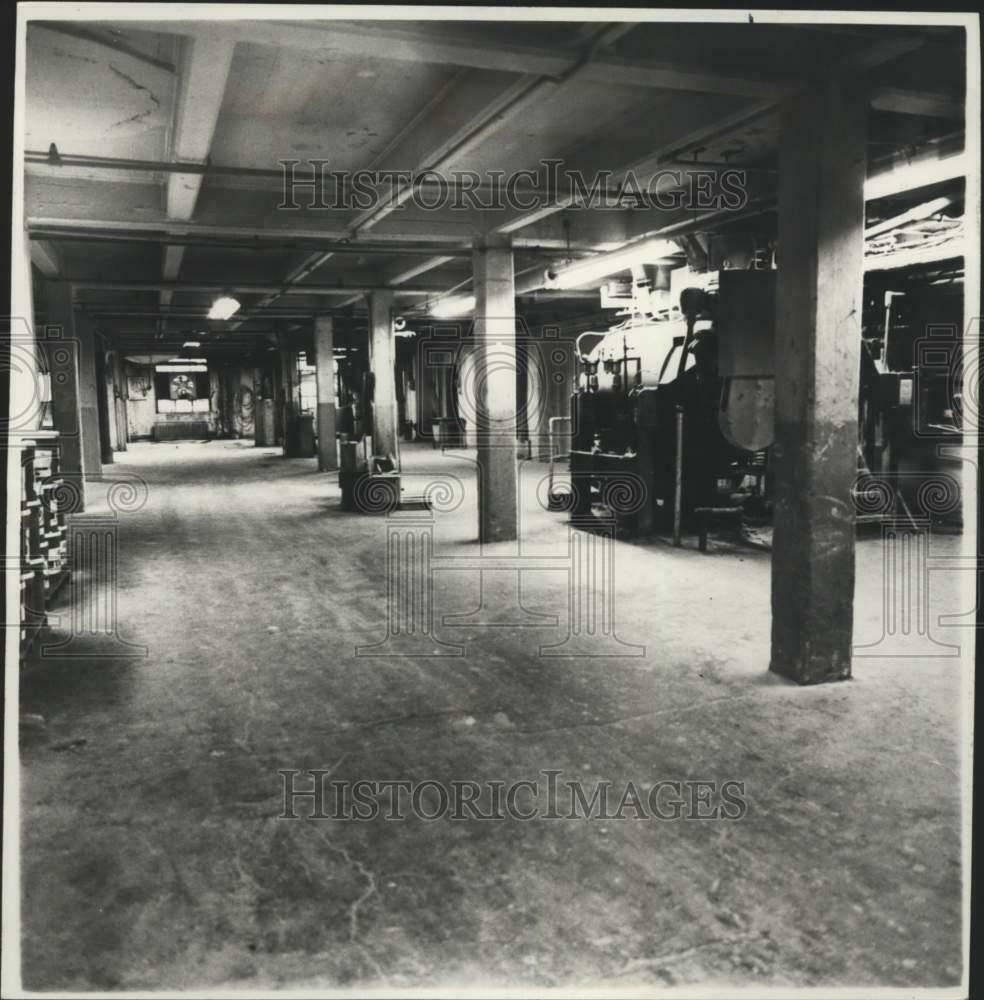

Railroad tracks ran past the silos, the Mill and the rotary calciners and then under the 5-story high, quarter-mile-long Building #4. The Building 4 railroad platform was built back into the hillside at water level. Here 100,000-pound rail cars of raw materials were unloaded; pallets of asbestos powder, for use in joint compound, and huge rolls of face paper for making wallboard. Finished products like plaster and joint cement were also loaded here for outbound shipment.

The columns in old Building 4 were closely spaced, making navigation of the tight traffic aisles a challenge, particularly when carrying pallets with loads piled so high the forklift operator couldn’t see over them. This made it necessary for the operators to drive backwards when loaded, which they tended to do at high speed. It was not uncommon for one of them to clip a column while turning a corner, carrying a tall pallet of asbestos bags. It would break off the corners of perhaps half a dozen bags, and as the truck hurried on along the quarter-mile-long main corridor, it left behind a trail of toxic asbestos dust. Eventually, someone came around and swept it up.

* * *

Directly above the Building 4 rail platform was a storage level, and above that was Grand Central, a quarter-mile long truck loading corridor on level 3, at the Richmond Terrace street level. Levels 4 and 5 were the wallboard plant. On level 5, a slurry of gypsum, fillers and additives was continuously spread onto a 4-foot-wide layer of face paper moving along a 400-foot-long conveyor. By the time it had reached the conveyor’s end, the slurry had hardened just enough to be guillotined into 8, 10 or 12-foot lengths. The raw sheets of wet wallboard then dropped down a set of inclined rollers into a 400-foot-long conveyor oven on the 4th floor, moving in the opposite direction. When the dried boards emerged, they were trimmed, taped and stacked for shipment across the street to the finished products warehouse by way of a conveyor belt bridge over Richmond Terrace.

In 1973, the wallboard plant was operating 6-2/3 days per week, working around the clock except for a single 8-hour maintenance shift on Sunday night. The main demand for the plant’s output was just across the harbor in lower Manhattan, a couple of blocks up from the Rector Street engineering office that I had left. Interior finishing work at the topped-out Twin Towers of the World Trade Center was running at full speed and the site sucked up truckloads of wallboard every week.

* * *

Continuing eastward, the railroad tracks exited from beneath Building 4 and ran on between the steep slope up to Richmond Terrace and the Paint and Perf-A-Tape departments in Buildings 5, 5A, 5B and 5C.

* * *

While dark rock ended up in either the stucco or wallboard departments, white rock followed a different path. From feeders below the silo floor, white rock was elevated 70 feet into the air and deposited onto the “High Line” belt conveyor, so named because it ran along a metal catwalk high above the roofs of all the other buildings. On clear days, the view of the City and the harbor from the High Line was spectacular.

The High Line ran more than 1/4 mile from the silos to Building 6, near the eastern end of the plant. Building 6 was a large, dark, 6-story empty shell, into which white rock was dumped on its way toward becoming various finished plaster products. The High Line catwalk entered Building 6 just below the roof level, and depending on the season, the rock might either be piled up nearly to the ceiling, or you might be looking down 6 stories into a building that was nearly empty. I stopped there often, watching the rock cascade off the end of the High Line belt in a mist of white dust. Above the crashing sound of the falling rock would come the rumbling of the building’s solitary piece of equipment, a yellow CAT bulldozer. Only the two tiny beacons of its headlights were visible through the veil of the perpetual gypsum snowstorm.

Six feeders under the floor of Building 6 moved the rock onto conveyors that ran through a leaky tunnel, below sea level, to various production departments. It was frequently flooded. The bulldozer was used to push the rock through openings in the floor to the feeders.

Gypsum may well the driest thing on earth. Get some in your shoes and it will make your feet so dry your skin cracks. Look up at the wrong moment, as some of it slides off an overhead beam ledge, and your eyes will burn for as long as it takes you to generate enough tears to first hydrate and to then wash out the crystallizing dust.

It took a special kind of person to sit there all day in a perpetual dust storm and operate the bulldozer. His name was Frank and he didn’t mind the harsh environment. To keep his throat and sensibilities properly lubricated, Frank kept a six-pack of beer under the seat. Even on busy days, when he would operate the bulldozer, run up six stories to keep clear some blockage on the high line, run down 7 flights to pump seawater out of the tunnel and then get back in the bulldozer to feed the conveyors, he would manage to polish off the six pack by the end of his shift. Often he didn’t even have time to leave the building to take a piss. It was best to speak to Frank from a good distance.

One day, the Company replaced the aging bulldozer with a new one. Unlike its predecessor it had an enclosed cab, which was nice, but the additional cost for air conditioning and filtration had been trimmed from the budget. When the cab proved too tall to pass under a pipe traversing the passageway into the building, it was removed, and that’s how it stayed. Frank seemed to like it better that way.

* * *

Beyond Building 6 was Building 7, an 1890 5-story structure reputed to be the second oldest poured concrete building in New York City, making it somewhat historically significant. At dock level, it was a dark cavern filled with abandoned-in-place, obsolete crushing and grinding equipment. Waist-deep drifts of white gypsum dust filled the space on either side of the only traffic aisle. The other floors were completely empty, with the exception of a large vibratory screen on the third floor. The heavy machine shook the floors and walls of the building as ten tons per hour of rock were separated into fine, medium and coarse particles. It shook so hard that two large, spreading cracks opened up in the northeast corner of the building, forming a distinct separation of a large pie-shaped wedge of the fourth and fifth floors.

As the screen continued to shake the building, there was growing danger of the whole corner breaking away and falling into the Kill Van Kull. To delay that, a steel cable had been installed; it was wrapped around an interior column on the fourth floor, then was fed out through the east wall crack, turning the detached corner, and then back in through the North wall crack, to be looped back and tied off to the same interior column. It was then drawn taut, pulling the corner back in part way and holding the building together.

My first capital project would be to write a request for emergency funding to tear down the collapsing corner. It was an impassioned piece of writing, citing not only potential employee injury or death, but also the likelihood that when the corner went down, it would pull out the column to which it was bound, taking down the rest of the building with it. Six months later I would receive my emergency funding, beginning my first foray into construction management and repair materials selection.

* * *

Building 8 was the Hydrocal plant, where high strength, fast-setting road-patching cement was made in pressurized stainless-steel autoclaves. It was a time and temperature critical process, and the batches of plaster heated in sulfuric acid had to be dumped when ready, or rock-hard Hydrocal would set up inside the autoclave, destroying a piece of equipment worth over a hundred thousand dollars.

In 1973, Consolidated Edison Co., New York City’s electric power utility company, boasted the highest electric power rates in the nation. Staten Island, New York City’s most rural borough, was undergoing something of a boom, and Con Ed was upgrading power lines along Richmond Terrace in response to increased demands. The construction led to frequent power failures at the plant.

About once a month, when the power failed in Building 8, plant maintenance crews had to get in there with wrenches and flashlights, disconnect the piping at the bottom of the Hydrocal autoclaves, and dump tons of hot acid and plaster onto the floor. The job had to be completed within 35 minutes. Any longer than that and the Hydrocal would set up in the autoclave. There were teams assigned to this task on call 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Almost invariably, power failures occurred late at night on weekends, but the teams always responded rapidly, and an autoclave was never lost.

The next day, the crew would come back in with jack hammers to break up the high strength plaster they had dumped on the floor the night before. I found it curious that the Hydrocal didn’t stick to the floor. The next month, the entire cycle would be repeated.

I was told that the bill for all the work was sent to the utility company, which presumably charged their millions of customers a fraction of a cent each to cover the cost. Nobody seemed to care or even notice.

* * *

The plant’s third floor was at Richmond Terrace street level, and there, near the center of the string of buildings, was the main Employee Entrance. Jack’s office sat to the immediate right of the entrance door, where he could observe and engage all who came and went. A lean, graying, ex-Navy SP whose priorities were laughter and security, Jack Ryan knew all of the plant’s 440 employees by sight and seemed to have some knowledge of just about everyone’s personal business. This made him a primary source of both useful information and entertainment. Although Jack seemed to find out just about everything that was happening or was going to happen, he never revealed his information sources.

Jack’s digestive system was a mess and it often caused him severe discomfort. Sometimes he would be sitting there, just talking, and his expression would suddenly become pained and he would turn deep red. Though he looked fit, his physical activities were restricted due to two prior heart attacks.

Jack came to my office on my second day, asking for help with an engineering problem. There had been rumors of layoffs in the Paint Department in the past month, and several suspicious fires had been set in a hallway storage area in Building 5. To catch the vandals, Jack had set up a hidden videotaping system in the hallway, with 24-hour elapsed-time videotape recording, but the recordings were coming out as nothing but static.

It was my first professional assignment to sort out the problem and Jack looked on as I intensely studied the machine and its hook-ups. The videotape recorder’s owner’s manual was almost unintelligible, apparently written by a Japanese technician who didn’t speak much English. Fortunately, I’d had some prior experience working with videotaping equipment during a summer job at the New York City Youth Services Agency during college, and so I had some idea of how these things were supposed to work.

After just a few minutes I could see that Jack had simply threaded the videotape in the recorder incorrectly. I rethreaded it, tested it, and there was the hallway on Jack’s monitor. He looked at the monitor, and then turned and looked me in the eye and spoke to me in his most earnest voice:

“I’ll be fucked”, he said, and then he burst out laughing. It proved contagious.

* * *

Entering the plant past Jack’s Office, I climbed the short flight of three stairs to the left and turned right through the doorway that led to “Grand Central”. The quarter-mile long interior corridor was a high speed forklift freeway, lined by truck loading dock doors on the street side and product storage bays on the other. All day long, the forklifts jumped in and out of the storage bays between the columns, picked up pallets of product, and then flew down the long corridor, depositing them into the proper trailers. Then they were off again, racing down Grand Central to retrieve the next pallet.

The operators worked with great speed and skill. Despite the congestion, there was never an accident involving a forklift. In fact, despite the enormous scale of the operation and the sheer power of the equipment used for burning, crushing, screening, conveying and packaging all those many tons per hour of plaster in its various forms, the plant had worked a million man hours without a lost time injury. It had not always been that way, and in fact, at one time serious injuries and job-related fatalities had occurred with some regularity at USG.

The tractor trailers backing into the loading bays on Richmond Terrace did not fare as well, however, and there were frequent accidents. The truck bays were short and narrow, constructed for a much earlier generation of trucks. Bringing a truck into its dock required traffic to be stopped in both directions on Richmond Terrace, and then the driver would back across both lanes, onto the sidewalk and into the bay. The street was too narrow to accommodate the full length of the truck, even once it had backed in, so drivers had to turn the wheels sharply, intentionally jackknifing the rig as it hit the loading dock door. It was a tricky maneuver, repeated many times each day, and there were frequent mishaps.

Every few days there would be a screech, and every few weeks one of the screeches would end in a BOOM. Then Jack would stroll out, survey the damage, look the driver in the eye and with cheeks reddening, he would speak in his most earnest tone of voice:

“Well I guess you’re fucked!” he’d say, and then burst out laughing.

It was all in a day’s work.

* * *

It took months to learn my way around the factory’s maze-like passages. Doorways lay hidden behind stacked pallets of finished goods or raw materials, and in dimly lit, obscure corners. Every floor within each building was different, just as each building was unique. I grew to really love the place, and I was always discovering something not previously known or noticed. It was indeed Wonderland, a giant fun house inhabited by the most curious characters, doing the most curious things. It was so different from the world of books, desks and papers, that was all I had known previously. Surreal as this world was, it was more real than anywhere I had ever been.

* * *

I remember the day the demolition crew began work on Building 7. Three men with jackhammers stood out on the failing corner’s roof, breaking the concrete below their feet. They were completely nonplussed, standing at the roof’s edge, on an unsound structure, six stories above the Kill, hammering away at the building until it crumbled. They worked untethered by any safety line that would save them from a deadly plunge if the entire corner were to let go. This started a disagreement.

“Under your contract you have to follow our safety rules”, I told the contractor’s Superintendent. “Those men have to wear safety harnesses attached to properly tied off safety lines.”

The Superintendent assured me they knew what they were doing and that they did this sort of thing all the time. I wasn’t compromising, though. The workers grumbled.

“If the building goes down I can just jump back onto the other side,” one insisted. “The ropes aren’t safe, they could get in my way”, he added with conviction. The others nodded in agreement. Their plan, if the concrete they were standing on was to fall, was to jump back onto the part of the building that was still standing.

“That safety stuff won’t help anyway, if you’re gonna go,” added another. “When your number is up it’s up.”

* * *

As we stood on the roof arguing, a yellow bulldozer crawled past the barricades erected below us on the dock. The building shook.

Later, I asked Frank what he thought he was doing, driving right into the roped-off area where tons of debris would be falling. Frank said the blocked off route was faster than going around the other way, and he wasn’t worried about getting hurt.

“When your number is up, it’s up” he said.

* * *

As I walked back through the Building 4 railroad platform, a worker was sweeping up a trail of grey dust in the main traffic aisle. Asbestos. His respirator was secured around his neck, but he had lowered it below his chin, so that he could smoke a cigarette while he swept.

* * *

Industrial Darwinism. The weak-minded will perish, the smart will survive. But I, too, must be counted among the occupationally stupid. For a year-and-a-half I worked in toxic dusty gypsum mills without ever having been given any means of respiratory protection. I had even been told that gypsum dust was healthy. I now know the odds that the asbestos particles still in my lungs from those days will eventually kill me.

At the time, Life seemed an endless string of days yet to come. Eventually we have to learn to live with the growing realization that we are on an collision course with mortality. For me, it meant there was no time to lose in getting on with realizing my dreams. I wouldn’t spend whatever time I had worrying about things that I am powerless to change. The end will come when it comes. When my number is up, it will unquestionably be up.

“What the hell you gonna do?” Jack would say, a smile spreading across his reddening face. “Just one more way you get fucked by the Company.”

You may as well laugh while you can still breathe.

* * *

Sal Cataldo the boiler man was a charming, fiftyish, earthy Italian man who wielded his personality freely, flirting with every attractive middle-aged woman in the plant. He was responsible for the operation and maintenance of the plant’s dozen-or-so boilers, which he managed as smoothly as his personal affairs. Sal’s boilers always ran fine.

The boiler room by the railroad tracks beneath the main offices had been converted to comfortable quarters, with the aid of some borrowed furniture and materials. There was a new linoleum floor, a small oven, a refrigerator, some comfortable easy chairs and a sofa. Sal also hooked up a stereo, and had run a set of speaker wires up through the ceiling into the accounting office above him. During his frequent visits upstairs, he would assure each of a number of women in Accounting that he was going to play something romantic especially for her. He would close with “Why don’t you come down and visit me later?”

Monotonous work is good fuel for fantasy, and there were frequent female guests in Sal’s boiler room living room. They would sit, and make small talk, as Sal opened a bottle of Chianti and poured a couple of glasses. They would hardly notice as one of Sal’s boilers fired up, running fine.

Sal’s culinary talents were often on display as well, and his favorite visitors were most fortunate when being treated to his famous boiler room cuisine. I was often invited, as Sal had a crush on the Engineering Department Secretary, Irene, and among her conditions for attending these affairs was my presence as something of a spoiler. Irene could talk endlessly about matters of no consequence, and often did. She was an attractive, voluptuous fiftyish blonde woman of Swedish descent who dressed impeccably, and that was enough to hook Sal. After a fine meal and a few glasses of wine she would loosen up a bit and I could excuse myself to go check in on some projects.

On quiet afternoons I would occasionally stop in to see Sal, and if everything was running fine he would pull a bottle from his desk drawer and a couple of cold beers from the refrigerator. We would sit there drinking boilermakers and talking shop for a while, and then just listen to the boilers, always running fine.

When the OPEC oil embargo of 1973 sent fuel prices skyrocketing, one of my jobs became to test all of Sal’s boilers for operating efficiency. I was provided with a little carbon dioxide/carbon monoxide tester and was sent off to adjust all of the various fuel burning equipment at the plant. On one particular day, I remember sitting on the sofa at Sal’s, having completed adjusting the boilers to their theoretical peak efficiency. About a half hour later, feeling very relaxed, I looked up to notice that the boilers were glowing hot, cherry red. We quickly jumped up to reverse my adjustments and I never messed with Sal’s boilers again. They always ran fine.

Sometimes I would run into Jack down there at Sal’s. It was the only place he could get a drink, strictly forbidden by his doctor. “What the hell,” Jack said, “when your number is up, it’s up.” His face reddened and we all laughed.

Jack and Sal had been friends for almost 20 years, and they operated from a place of deep trust based on keeping a multitude of each other’s secrets over the course of all that time. Between them, they seemed to know just about everything that was happening or going to happen to just about everyone at the plant. Neither of them would ever divulge their sources, however.

But one lazy day, during which too much time had been spent at Sal’s, I pressed Jack to tell me just how the hell he knew all the things he knew. Jack looked at me earnestly and said “Hugo told me”. His face reddened until he could hold back the laughter no longer. Hugo was the plant janitor, who worked mostly nights cleaning offices, hallways and bathrooms. He couldn’t read, write or speak a word of English, as far as anyone knew.

From that day on, every time Jack shared a bit of inside knowledge with me, he began with “Hugo told me…” And invariably, the things that Hugo was alleged to have told him would turn out to be true.

* * *

Sal’s boiler room had a secret exit, but everyone knew about it, so it wasn’t much of a secret. Through a side door that opened to the embankment below Richmond Terrace, one could climb a ten foot ladder up to street level and exit through a gate in the chain link fence there. I was told that some years earlier, when a union had been briefly established at the plant, workers would sneak out Sal’s secret exit at the end of the work day on Friday afternoon to avoid the union rep collecting dues at the main gate. These days it was just mostly Sal that used the secret exit, for comings and goings that nobody seemed to question.

A great deal was said about things that had happened during the period when there had been a union. I doubted that much of it was true, but the part about avoiding the dues collector seemed plausible. I had once done the same thing during a high school summer job in a supermarket, where my weekly union dues amounted to more than the 15 cents an hour over minimum wage I was earning. I figured I didn’t need to pay a union to help me net less than the $1.85 an hour minimum wage.

I changed my mind, though, when a union-filed wage-hour complaint got me a week’s extra pay. The New York State Labor Department determined that the supermarket’s management had illegally deducted pay for break times.

I have no illusions about unions, for better or worse. Historically, they were the only protection a worker had against unsafe or unhealthy working conditions, and it was his only hope of being treated fairly. But in some places unions are little more than an extortion racket, in some cases run for the profit of organized criminals.

I have no illusions about corporate management either. While industry creates jobs and contributes to our economic vitality, some are capable of almost unspeakable acts against their workers and communities. There can be health-destroying assignments given to senior workers nearing retirement, perhaps to minimize the benefits that will ultimately be collected. There were layoffs of more costly senior employees in one department even while another department in the same plant was hiring. Plant safety rules that cannot possibly be followed could be used as a means of fixing blame after someone has been hurt or worse.

There can be personal abuses by management as well. The girlfriend-subordinate who is no longer the girlfriend finds herself transferred or fired. Perhaps another is pressured to become the girlfriend.

In 1973, in the early days of OSHA and before sexual harassment lawsuits came into vogue, all these things were possible and all were rumored to have occurred. I had no way of knowing what was true and what was a fabrication.

I know now that there are places where labor and management work effectively together, both in unionized and non-unionized environments. There are also places that have been ruined by the excesses on either or both sides. What is needed most is often what is hardest to come by: reasonable people exercising common sense.

In the four years following the collapse of the union at the U. S. Gypsum Company in Staten Island, the factory had been running at full steam, 6-2/3 days a week, 3 shifts a day. As the 1350-foot Twin Towers went up, the New Brighton plant cranked out truckloads of wallboard and joint compound, destined for a short trip across New York harbor to lower Manhattan. For four years there had been steady work, annual pay increases and relative contentment among the workers.

But as the Spring of 1974 approached, there were ominous signs of changes ahead for the worse. The Towers were completed, curtailing the demand for our products. Crude oil prices had skyrocketed in response to an OPEC oil embargo, designed to punish the United States for its support of Israel in the Yom Kippur war. This led to an economic condition that came to be known as stagflation – stagnancy due to rising prices for everything, during a period of inflation, where the price of everything continued to rise rapidly in spite of weak demand. Gas lines were forming, and shortages kept people from being able to get to work, much less travel for leisure or non-essential business. Utility rates took a major hike. In fact, nothing had a firm price any more. If I had to order a new pump, the price quoted was today’s price, but the price we would actually have to pay would be the price in effect on the day the pump was delivered. God knew what that would be.

“Now hear this”, Jack announced from a megaphone made of rolled up reports, as he entered my office one April morning. “You are about to see a totally new way to get fucked by the company.”

I knew it was true. Jack had gotten the word from Hugo. Official notices wouldn’t be posted until the following Monday. The plant would be closing.

* * *

A fire broke out in the paint department in an empty bag storage area. Though the sprinklers went off, Jack ordered the building evacuated. Hundreds of workers mulled around on Richmond Terrace while the Fire Department went about their business, checking for embers amidst the drenched paper.

It was cold that morning and I went off seeking warmth and coffee, across the street at Dirty Dan’s luncheonette. There I found Sal, entertaining a half-dozen ladies from Accounting. He gestured to me to join them, ordered me a cup, and poured in a little something extra from a flask he produced from his coat pocket.

As we watched the fire trucks, the shifting crowd and the commotion on the street, Sal told me that all of this was a considerably tamer scene than the one he had seen several years ago, when the union was being broken. He talked about beatings of scabs, shots being fired, and a manager’s car set ablaze. To hear him tell it, it had been a small war. I had no idea if any of it was true.

These workers, on this day, had no heart for warfare. The mood in the country was “things are tough all over”, and there was a pervasive belief that things had only begun to get worse. When the fire trucks left, everyone went back to work. It was best to make a few dollars while one still could.

* * *

“No shit”, Jack said, exhibiting an unusually sincere sense of gravity. “This is it”.

“How do you know?” I asked.

“I have my ways”, he answered. Then he grinned a little. “Hugo says June 16th at 5 PM.”

* * *

“Well we all know things are tough all over”, plant manager J. C. Fountas began. Old white faces and young black ones stared back at him dully. Many were covered in a layer of white dust, making it hard to tell them apart.

“The Company has been fighting hard to keep things going strong here”, J. C. continued. “We’ve been meeting with the power company and the Mayor’s office for several months trying to work things out. We’ve tried to get a reassessment to reduce our property taxes, and we’ve applied for assistance from the Economic Development Administration…”

The men stood quietly, staring back blankly as Fountas went on for 15 minutes. They already knew. The Company’s valiant efforts notwithstanding, in the face of a major market downturn, skyrocketing energy costs and new pollution control equipment requirements, they could hardly be blamed for what was about to happen. When the words were finally spoken it was anti-climactic.

“…so as of five PM on June 16th, 1974, production operations at the New Brighton plant will be permanently terminated.”

A few knowing glances and half-smiles were exchanged. Hugo had hit it right on the head.

Then the Personnel Manager got up and talked about benefits and termination pay. It wasn’t going to be much. Then it was over and they all went back to work. I stayed behind to talk briefly to Mike Tomasello, who told me he had been transferred to the Boston plant. I wished him luck and we promised to stay in touch, and for some time after we actually would.

“There’s something else”, Jack told me, as he grabbed me by the sleeve on my way out the door. “Hugo says you’re being transferred to Philadelphia.”

I had no reason to doubt it. Until that moment, I had been certain that I would spend all of my life in New York. Things never turn out the way we expect.

* * *

“You can’t leave New York”, my mother insisted. “There’ll be nothing to eat!”

* * *

The last day was one of the saddest experiences I can remember in my working life. Among the 440 employees of the New Brighton plant were many who had come to work there at age 16, and were still there after 20, 30, 40 and in some cases more than 45 years. The Company had long encouraged employees to recruit their family members to work there, and there were large multi-generational clans of men who had never worked anywhere else. Fathers and sons, cousins, uncles and nephews, all gathered on the street after the machines stopped for the last time, and they cried.

It is a scene that has since been repeated in plant after plant, industry after industry, in town after town in every corner of America. One day at a time, one factory at a time, we have been losing our capacity to make things. Fewer and fewer of us know how to make anything, and I fear we are approaching the day when nobody will know how anything works, much less how to fix it.

* * *

Within a week of my arrival in Philadelphia I came down with pneumonia. The plant was old, small, dirty and inefficient, and the engineering office sat in the middle of a dry mixing process area with dust everywhere. My first thought was that I was already dying of asbestos exposure. Maybe it was the giant bloody wads of thick yellow-gray sputum that erupted out of my chest every few minutes.

The Company’s lung specialist assured me that all I needed was total rest, drugs and good nutrition. When I returned to work, a couple of weeks later, I expressed my concerns to the Personnel Manager.

“You know how we take care of our own at the Company,” he tried to assure me.

But all I could think to answer was “No, I really don’t.”

* * *

Soon afterwards, the Philadelphia Plant Engineer sent me back to New Brighton with the plant pickup truck, on an equipment scavenging mission. The place was in the process of being dismantled by a small crew of mechanics, and it was already taking on the look and feel of a ghost town.

After retrieving the motor I had come for, I took a final tour, starting at the silos, all empty now. I climbed the stairs to the High Line, idle now. I walked its length to Building 6, and looked down into its empty depth, 6 stories down. Frank’s yellow bulldozer was gone, too.

Building 7 was also strangely quiet. I revisited the blocked-up corner where a great deal of additional building had once stood, and inspected the columns where a steel tension cable had once held back tons of masonry from falling. The triple deck screen there was silent, joining the abandoned-in-place equipment from generations past.

I learned that Jack had been transferred to the new paint plant in Port Reading, New Jersey. His office by the entrance door seemed much smaller without him in it.

My last stop was Sal’s boiler room, and I found him there in his usual good spirits. He smiled, slid open his desk’s top drawer and produced a bottle and two clean glasses.

“I’m opening a seafood restaurant with my cousin on Forest Avenue”, Sal said. “Come down for dinner some time. I’ll make you something special.”

* * *

As the battered white USG pickup truck sped down the New Jersey Turnpike, I began wondering just what the hell I was doing in Philadelphia. I was convinced my work environment had made me seriously ill. The work was routine and offered little interest or challenge. And if the dust didn’t kill me, I was sure I would be driven crazy by the constant rumble of some unseen machine that rattled the floors and walls around me all day long.

Just as I was thinking I should turn around and go back to New York, the pickup truck bucked, the engine died, and I found myself coasting to a stop along the shoulder, 1 mile from Exit 8A in Cranbury, right under a sign that said so. So I did what people did in the days before cell phones. I got out and hitched a ride to the next rest area, where I called for help. Two hours later I was back on the road to Philly. Someone else would go get the dead pickup later that day.

I knew I needed to get out. My life was headed in the wrong direction. I could put up with inconvenience, discomfort, illness or dislocation, if I felt like I was moving forward to something that was better. What I couldn’t tolerate was endless boredom and the sense that things were actually getting a lot worse.

I realized how horribly ungrateful I must seem. Over four hundred people had just lost their jobs in New Brighton and I was one of the lucky handful of professional staff the Company considered too valuable to lose. Still, at 22 years old it was no time for me to be running my life by looking backwards. I needed out.

A funny thing happened on the way to planning my next step in life. Before I could even work up a resume and begin to make contacts that might lead to a change, the Philadelphia Plant Manager sent out a memo to everyone to attend a general meeting.

“Well, we all know that things are tough all over,” he began, eventually getting to the point of announcing the closure of the Philadelphia plant. Nobody reacted, they seemed to already know. And just like that, another 50 people’s lives changed.

I don’t remember how I was given the news of my own next mission. I may simply have been told by my supervisor, the Plant Engineer. Or it may have been leaked to me by the Maintenance Foreman, who, like Jack at the New Brighton plant, always seemed to know everything that was happening.

Memories are a funny thing, and at some point mine may has undoubtedly taken some artistic license. I often imagine that as the crowd filed slowly out of that cramped, smoky Philadelphia conference room, that I felt a hand on my sleeve, and as I turned to see who it was, I heard a quiet voice ask:

“You Edison?”

I nodded.

“You go Baltimore now” the man said in broken English, while gathering up his broom and dustpan.

* * *

“I am the kiss of death,” I announced to my new boss, upon my arrival in Baltimore. It didn’t seem to faze old Fred, though. Not much did. I liked that.

“I’m 72 years old and don’t feel a day over 80,” he told me and just about everyone else he met. We were both recent transplants from out of town, so we often went to dinner together in those first few weeks. Fred always drank me under the table. Then he would use the same 72/80 line on our waitress and start calling her “daughter”. A few drinks later I became “son”. It could have been obnoxious, but the girls found him charming, because he was.

I began to feel like things were getting better again, and Fred was teaching me a lot. He had been brought out of retirement to help start up a major expansion of the Baltimore plant, the Company’s newest and most efficient. I was learning Construction Management first-hand from a seasoned professional. I felt like Life’s proper natural upward arc was being restored. Then suddenly, one day, they forced Fred back into retirement. He seemed surprised. I didn’t like that.

I liked his replacement even less. When he didn’t take his high blood pressure medication he was irritable, combative and demeaning. When he did, he just seemed mentally deficient. I doubted that he had even completed a high school education and he made it clear he had demons to battle and scores to settle.

The mean side of Gene Guthrie was bad. I was apparently the first college graduate ever assigned to his “command”, and it amused him to publicly order me to do things like sweep up the office trailer floor or go get him coffee.

“That’s my college boy,” he said to the iron workers’ foreman. The man winced, and asked me if I would join him and his crew just outside the gate after quitting time. I gladly accepted.

“What an asshole that guy is,” he said to me, later that afternoon, handing me a beer. After a cold day of walking icy six inch wide beams a hundred feet above the concrete base of the new building expansion, with the wind blowing in off Chesapeake Bay, the men got together to decompress, have a drink and tell stories.

Most of the stories were just really bad dirty jokes, but then the foreman told the tale of a day even colder than this day, when he was working with a new man, trying to set steel in an icy wind.

“He took that 12-pound mall, and just as he was about to hammer that beam into place, the wind kicked up, and the guy lost his balance and dropped the mall 100 feet to the ground, where it shattered,” the foreman said. “So he had to go back down and get another mall.“

“Half an hour later, there we were, back up on the steel, trying to set that beam. And when the new guy went to hammer that beam in place, the wind kicked up again, and he began to slip and dropped the new mall, 100 feet to the ground, and it shattered too.”

“So he had to go down again and get another one and I told him he better not let this one go. By then the wind was really blowing and the beam was covered with ice. He went to hammer the beam into place and he slipped on the ice, but this time he didn’t let go of the mall. I saw him just about to go off the edge from the corner of my eye and grabbed him by the belt and I pulled him back up, still hanging on to that mall”.

The new guy was screaming “Thank you!” “You saved my life!” “You saved my life!”

But I just told him: “Hell, that was the last mall we had.”

* * *

Not long after that, Guthrie was put on a Valium prescription, and suddenly, for a while, anything I wanted to do was fine.

“Should I go get your car washed?” I asked, one bright Friday morning.

“Sure”, he smiled and tossed me the keys to his Company-issued green Chevy Impala.

It was a cold but sunny day and I drove down to the inner harbor for lunch and then made my way out to the Eastern shore. It was like I was 9 again, on a one-way trip to the bathroom to avoid Mr. Lewinson’s boring 4th grade Bible class. When I returned at a quarter to five that afternoon, the car was washed, the gas tank was full, and the smile was gone from Guthrie’s face.

“Where’ve you been?”

I shrugged. It was time to go home.

As the Valium lost its effectiveness, the smiles became fewer and further apart. I began to get headaches and quickly exhausted a year’s supply of sick days. Between the bad karma and the boredom, things only got worse. I got so lost in my own thoughts that when I got called in to the Personnel Manager’s office in connection with an incident involving two employees having sex in a rail car that I had supposedly walked in on, I had to sheepishly admit that I hadn’t even noticed.

My old boss from Staten Island, Paul Stevens, visited the Baltimore plant one day, and we were happy to see each other. In the few moments we had to talk I shared with him just how bad my situation had become in Baltimore, and he tried to encourage me to hang in there, assuring me that things would change for the better. But he didn’t seem all that happy with his new position either.

Time to go. I prepared new resumes and a few weeks later I was on the road again. Goodbye redneck ignoramus boss, goodbye dusty gypsum mills, goodbye Baltimore. An interview was arranged, an offer was tendered and accepted, and it was Hello Nestle Foods, white lab coats and beautiful northwestern Connecticut.

So just like that, everything changed.

I was 23 and still apparently healthy. Lots of Life still lay ahead. There was plenty of time for things to get back on track and to get progressively better. I was hopeful that the bad times were now behind me.

As it turned out, they had only begun.

If we knew exactly what we were in for, would anyone ever do anything?

So it goes, we make what we made since the world began

John Perry Barlow

Nothing more, the love of women, work of men

Seasons round, creatures great and small,

Up and down, as we rise and fall

“Weather Report Suite II”